The Evolution of GiveWell's Research

September 09, 2019

Since 2007, GiveWell has recommended charities that directly deliver interventions to beneficiaries, with clear advantages that are relatively easy to measure. Recently, it began looking into interventions that are harder to measure — but might be much more cost-effective.

Below is a transcript of the talk, which we have lightly edited for clarity. You may also watch it on YouTube or discuss it on the EA Forum.

The Talk

My name is James. I'm a researcher at GiveWell and I'm going to provide a quick update on some of the work we're currently doing to investigate giving opportunities related to policy. [Since most of you are familiar with GiveWell's previous work, I won’t] go over what GiveWell has done in the past.

First I'll talk about how and why GiveWell is changing. Then I’ll cover our current work, with a focus on policy and, in particular, public health regulation. Finally, I'll talk about what this means for GiveWell over the long term, and also what it might mean for [you].

GiveWell's mission is to find the best giving opportunities we possibly can to help the global poor. We publish our research and rationale online, so donors can [more judiciously] choose where to direct their funds.

In the past, we've generally focused on direct delivery [of interventions], funding organizations that do work like bednet distribution, cash transfers, or Vitamin A supplementation. That is because the two people who founded GiveWell in 2007 had very little experience in the global health and development space. Therefore, they wanted to work in areas that were easier to quantify and compare; this also meant that donors could trust GiveWell’s judgment [as it was based largely on calculation rather than subjective evaluation].

While there are still a lot of judgment calls involved in deciding which direct-delivery giving opportunities are the most cost-effective, I think it is generally a more objective process than selecting policy-related opportunities. Tackling policy work requires addressing some thorny questions.

In the past year, two things have changed for GiveWell:

- The organization has been doing this work for twelve years now, so we have a lot more experience in global health and development. We've recently hired people who are well-equipped to help us with [policy] work.

- We have built up a level of trust with donors that allows us to make more subjective judgment calls; they have reason to believe that we're not just talking nonsense.

So what does this mean in terms of the areas that are now within our scope? One way of thinking about the spaces [we’re exploring] is to carve it into three areas:

- Policy work, which I’ll talk about today.

- Direct interventions we previously hadn’t considered. Direct interventions with less experimental evidence might, for example, include those in the education sector — where it is a lot harder to draw conclusions than it is in the health sector because [it’s hard to generalize results from one location to other locations]. Previously, that caused us to drop that research and determine that we couldn’t come to strong conclusions. Now we are asking, “What is our best guess? How can we make reasonable judgments in areas that are harder to evaluate?”

- Science. We haven't made a lot of progress in this area yet, but we are considering which technologies in the field of science we think could have a large impact on the global poor. For example, we are looking into whether there are opportunities to fund improved diagnostic tools for pneumonia.

With policy as the focus of this talk, I’ll give a brief overview of why [GiveWell decided to look into it].

As a general caveat up front, I have only 20 minutes to talk about an entire year's work, so I'm not going to get into as much detail as you would typically expect from GiveWell. We also haven't yet written publicly about this work.

So why [focus on] policy? Broadly, there are two reasons why we think this might be an area in which we can find better giving opportunities:

- There is a very strong intuitive case for it. A small amount of funding that is [appropriately] directed to change policy could potentially improve a lot of lives, because policies often cover an entire country, and for a long time. Changes in policy may last many years into the future without the need for additional philanthropic assistance.

- There are some interventions that can only be done by governments. Thankfully, NGOs don't have the power to go into a low-income country and just change the law. But that means that if you want to do particular things, you have to work with governments.

We're aware that this is going to be a challenging area, both to work in and assess. There are a number of reasons for that. We think there's a high chance of failure. I wouldn't be surprised if many of the grants we recommend end up having close to zero effect.

[The first issue is that] it's very hard to predict when [good opportunities to set new policy] will open up, and whether the particular context will [allow us to make] a difference.

The second issue is that causal attribution to specific actors is particularly hard to determine. When a policy change happens, it's difficult to say, “This group was 20% responsible for it” or “This group was 30% responsible.” We haven’t concluded on how to do that. A lot of our reasoning is likely to be more qualitative than it was previously.

The third thing that I think makes policy particularly challenging is it can be difficult — not always, but often — to evaluate a particular policy change through an experimental lens. If a policy is put into place in a country, it will often [affect] the whole country at the same time. There won’t be a good treatment-control comparison.

The fourth challenge is something we must be very conscious of: the risk of excessive paternalism. We need to understand that, as outsiders, we have limited knowledge. We must ensure that we work through democratic institutions to the greatest extent possible.

That's a brief update about why GiveWell is working in this area. Next, I'll talk about our tentative conclusions so far.

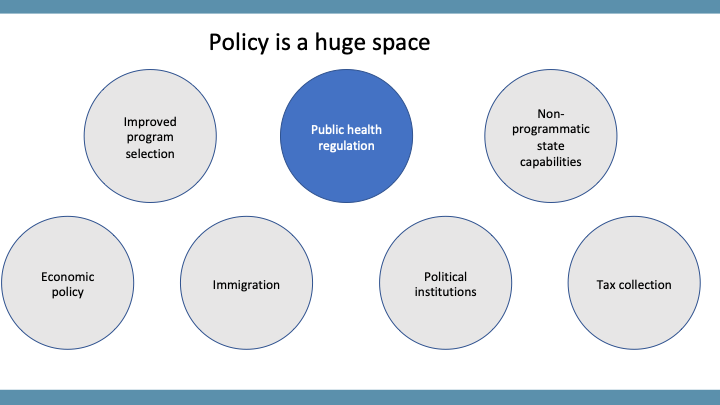

First of all, policy is a huge space. It's not just one thing, and there are multiple ways of carving up the space. What are some things you could do to improve how effectively governments operate within a country?

One approach might be to help governments choose better programs. You might want to fund a group to evaluate different programs and give advice to the government about which things could be the most effective. If you can improve the effectiveness of a government’s spending, that could be very impactful.

There are also opportunities to influence economic policies: trade policy, fiscal policy, industrial policy, immigration. High-income countries follow certain policies that, for poorer countries and political institutions, often have negative externalities. If we figure out [what those are], I think we will have done very well. Governments don’t just run [public welfare] programs. Improving the tax collection system, the judiciary system, how the administration works, and various other functions of the government could also be very impactful.

The area we chose to focus on first is public health regulation. There are a few reasons for that:

- We think it's potentially a particularly impactful area. For example, if we look back in the past, there are examples of tobacco taxation [being beneficial]. There is fairly compelling evidence that, while not experimental, indicates that increases in tobacco taxation generally result in decreased rates of tobacco-related illnesses.

- We also think there are opportunities for outside philanthropic assistance to play a role. It’s not just about funding grassroots advocacy campaigns. It's also about providing technical assistance and research, and there are a lot of areas where outside assistance might be [helpful].

- We wanted to start in a space that [reflects] where GiveWell is and builds on our experience — a space where we could use the tools and abilities that we have built up over time to make good decisions. What perhaps distinguishes public health regulation from many of the other areas we may have chosen is that it is fairly proximate to impact. With political institutions, a lot of things must happen before changes filter through and improve people's lives. Health interventions are fairly well-defined, so you might be able to take evidence from one setting and apply it to another, [scaling your impact more quickly than you might have been able to in other policy areas].

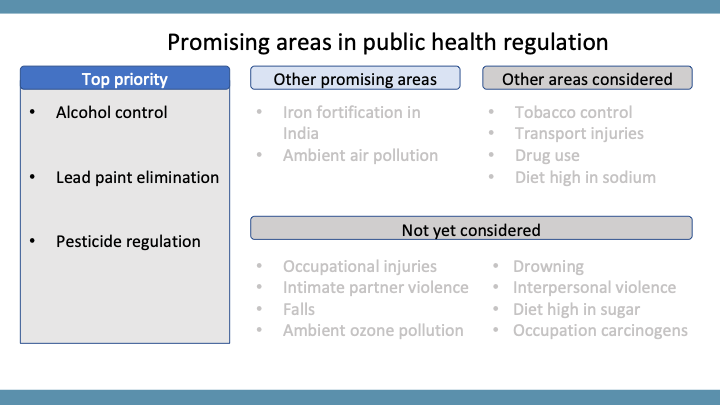

In our work so far, we have tried to find the areas within public health regulation that we think GiveWell might want to focus on in the future.

We started with a long list that we took from the Global Burden of Disease Institute and went through different risk factors, as well as causes of death and disability, and considered whether there are regulatory opportunities that could help to alleviate this burden. Using that heuristic, we narrowed down the list to nine areas. We also identified a number of other areas that we hope to come back to in the future.

The primary way that we distinguished between those nine areas was to ask: How much money is currently being spent on this? That question was a proxy for neglect. [We also considered] the current disease burden of each area.

Once we went through that process, three areas really stood out:

- Alcohol control;

- Lead paint elimination; and

- Pesticide regulation.

I will note that there were a number of difficulties and limitations of this methodology. We hope to go back and refine it over time. But I think this is an example of GiveWell’s [conscious decision], when doing early work, to take a broad approach rather than doing deep research in a single area. We often find that once you've [done that type of deep dive], you become attached to that area. To avoid that, we start broad and shallow.

Generally, if you take how much was spent on those three areas — alcohol control, lead paint elimination, and pesticide regulation — divide it by the [impact of the problem on people] and then compare the result to the other areas we looked at, they were generally receiving three to five times less [funding] than some of the other areas we looked at. All three are roughly similar on that metric.

Here is a brief overview of alcohol control:

Alcohol, according to the Global Burden of Disease Institute, is responsible for about 1.2 million deaths every year in low- and lower middle-income countries. Our best guess is that under $5 million a year is spent specifically on advocacy for better alcohol policies. Compare that to tobacco control, which is an area that has received a lot more attention. Tobacco is responsible for about one and a half times more burden of disease than alcohol, but about 15 times as much is spent on it every year. So alcohol looks to be a particularly promising area. It is superficially similar to tobacco in many ways (although there are also important differences), but hasn't received nearly as much attention.

We're looking at what we could do in this area — the best buys. There [are many factors] we need to look into more deeply, such as alcohol taxes, marketing restrictions, and restrictions on when you can purchase alcohol.

We have a number of remaining questions in this area. We haven't fully vetted the Global Burden of Disease Institute estimates, and we also want to be careful and consider the number of people who enjoy alcohol. How might we factor that into the cost-benefit analysis?

I'd say what distinguishes alcohol from the other two areas is the very large burden of disease it carries. The other two are more “niche” burdens, but perform well on the “[funding] neglect” criterion.

Lead paint elimination has been [a big area of interest] in the U.S. for a while, but I hadn't heard of it in the U.K., where I grew up. There is some evidence, consistent with what we know about lead, that exposure to lead paint during childhood can have large effects on people's cognitive development — and that can affect their earnings later in life. That comes from a series of multivariate regressions, which is not completely dispositive, but there are reasons to think that this might be true. We know that lead is a toxic metal. We know that a lot of children in low-income countries have high levels of lead in their blood. And we know this has to be coming from [something in the environment], because the natural level without exposure to lead is very close to zero, and those countries have, in many cases, already eliminated lead in gasoline.

Paint is widely considered to be one of the most important contributors to [the high levels of lead in people’s blood]. We think under $3 million is spent on lead paint elimination, and it appears to be an area that has some traction. A number of countries in the last 20 years have brought in new restrictions.

The third area, pesticide regulation, is something I talked about at last year’s EA Global conference. It's an area in which we've already made a grant. The case for this focus area [rests on] reducing suicide. About 150,000 people die every year from deliberately ingesting pesticide. There's some evidence from Sri Lanka in the 1990s, which used to have one of the highest suicide rates in the world, that targeted restrictions on certain pesticides coincided with a reduction in suicides of about 50%. That is one of the largest sustained reductions in suicide in history.

That is literally a time trend, so the evidence isn't [ideal]. But it's backed up by the medical records. You see a shift in the pesticides people drink in suicide attempts, from those very high in toxicity to those lower in toxicity, resulting in an improvement in the survival rate. If people survive a suicide attempt, more often than not, they won’t try again.

These three areas are our current top priorities. We're definitely going to come back to other areas. There are two I'm particularly excited about. One is iron fortification in India, which has a very high burden of iron deficiency anemia. Governments can pass certain regulations to mandate that producers of wheat or rice, for example, put various vitamins into those products before they get to the table. We want to do more work on that scenario. Another one that we found [promising but] particularly challenging to assess is ambient air pollution, which has a very large burden of disease. That is tricky, because a lot of the things that you would do to reduce particulate matter — which directly impacts human health from air pollution — would overlap substantially with what you might do to reduce CO₂ emissions. It was challenging to assess within our framework, because we had to ask: Do we include all the funding that is spent on CO₂ reduction?

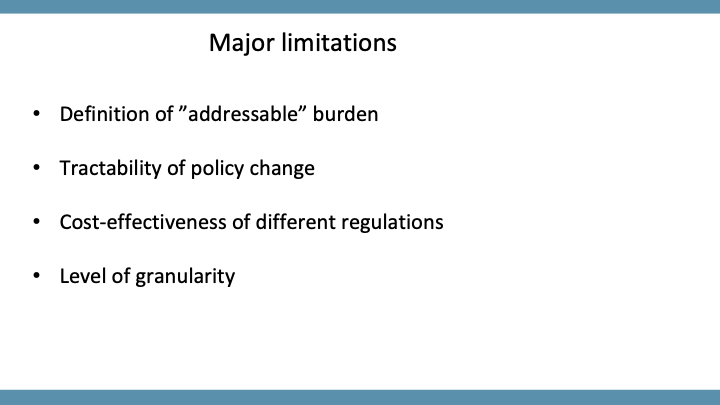

There are problems with our methodology worth noting that we hope to go back to and improve on in the future:

- We generally use the total burden of disease as a proxy for importance. I think that does leave something out. For example, we're never going to reduce alcohol consumption to zero, or at least not in the short term, and it's not even obvious that we should try to. So we might be overweighting some areas just because they have a large burden of disease, even if plausibly we could only impact them by a small amount, like 10%.

- It is very challenging to assess how tractable particular policy changes might be. We took this into account somewhat [but perhaps not enough]. For example, lead paint elimination appears to be an area in which industry is generally on board. That did play some role in our prioritization, but it's very hard to predict which policies will be tractable at which times, and policy windows often open for a very short time. We think we could be missing [important factors] if we deprioritized an area just because we think it's hard to gain traction on right now.

- I think we still have a lot more work to do on the cost-effectiveness of different regulations. In the future, we will do that before investing in an area.

- We're considering areas at different levels of granularity. If, instead of looking at pesticide suicide specifically, we looked at suicide in general, it's possible we would have come to different answers. In deprioritizing some of the areas we explored at a very broad level, we may have [overlooked] specific things within them that are very [worthwhile].

What does all of this mean to GiveWell? And what might it mean to you?

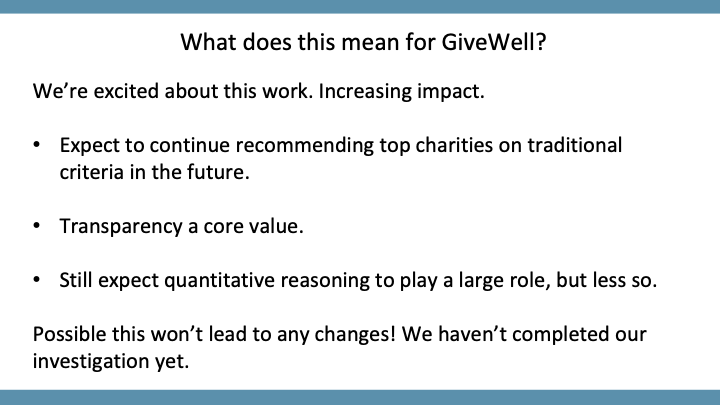

We're really excited about this work. We think it's likely to lead us to becoming far more cost-effective than we currently are, and to recommend giving opportunities that are far better than what we currently recommend.

We do expect to continue recommending top charities using our traditional criteria in the future. We don't think anything about that is going to change, at least in the near term, although it might well be that if we identify enough policy-related opportunities, the amount of funding that goes to our top charities will be diminished. We still want to keep transparency as a core value. We're still going to commit to writing up any recommendations we make in great detail.

We’re also cognizant of the fact that there will be more instances of news that will be difficult to share. GiveWell has never really had enemies before. There aren't groups trying to stop bednets from being distributed. That might not be the case in areas like alcohol or tobacco, where there are well-funded industry groups with strong positions. I think we have to be very careful about what we can share and when, while maintaining a commitment to transparency to the extent that we can.

We still expect quantitative reasoning to play a large role in our work. We still find using spreadsheets very useful. But we are going to put less weight on those than we do when we reason through direct interventions. And we know that some of the assumptions that [underlie the new work] will be very difficult to justify.

It's also possible that this work won't lead to any changes. We haven't completed our investigations yet and we want to keep an open mind. We don’t want to [take on this new work] just because it's exciting and shiny. My best guess is that we will be able to find opportunities in this area; in fact, we have already made two grants. But it’s early days.

Before I finish up, I want to mention that I've focused on the public health regulation work we've done here. We have also made two grants in policy already. One was to the Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention, which I mentioned. The other was to the Innovation in Government Initiative. That organization is very exciting.

So what does this mean for you?

I think two things. One, if you are a donor, I expect that GiveWell will present a different suite of giving opportunities within the next year or two. We're uncertain exactly how we're going to do that. It could be [in the form of] some recommendations for charities we think are great. It's more likely, I think, to be [an approach whereby you could] contribute to a fund, and then we would use that to fund opportunities that haven't been defined in advance. With these kinds of opportunities, it's less about every dollar having a marginal impact. Specific grant funding to do specific activities might be a better approach.

The other implication is that we're hiring. We're particularly excited for people to apply who are involved in the effective altruism community. We've had a lot of success with that in the past. We're mostly going to be looking for experienced researchers, managers, and people who have worked in global health and development before. But we also expect to be hiring a number of junior staff straight out of college.

Moderator: The first question from the audience: What is your plan for when GiveWell's ideas or agendas run afoul of the preferences of politically powerful or well-funded competing interests?

James: It's a good question. I don't think I can generalize. Those competing interests will be different in each case. So I’m sorry, but I'm not going to be able to give a very satisfying answer to this, except to say that it's going to be domain-specific. It's going to depend on the specific grant, and we think that many of the best people to be making those kinds of tactical decisions on the ground [will likely be the people we’ve funded, rather than our own researchers]. So we want to be very humble. We need to recognize what we're good at and what we don't know about, and not micromanage grantees.

Moderator: Do you see opportunities in policy intervention that affect multiple cause areas simultaneously, such as within affirmative voting methods?

James: Yes. I don't know much about affirmative voting methods in particular, but I think one of the things that's challenging is that, [in order to make decisions about what to fund], we carve up the policy space. But that doesn't reflect reality. It's a very simplified model of reality. So for at least some of these [policy areas], you can think about impact in terms of a pyramid. Some things are very much at the top and will affect multiple other things. For example, if you could improve political institutions in a country, that's going to have some effect on health eventually. There are causal areas that work that way.

We decided to start, as I said, in an area that is fairly specific and proximate to impact, because we think that's the most tractable thing to do in the short term. But in the long term, we'd love to look at areas that are much broader.

Moderator: Last question: How much paternalism is appropriate and not excessive?

James: I was afraid someone might ask that. I think one distinction I'd make is — and I apologize if I'm butchering the language here — between what I would call “paternalism” and what I would call a “neocolonialist attitude.” To me, paternalism is about individuals and individual restrictions in liberty, whereas a neocolonialist attitude might be closer to not respecting the democratic norms of a country.

To address the paternalism question, public health regulation often does have a paternalistic element. There are some nuances around that. For example, with tobacco taxes, there was strong pushback early on, until the secondhand smoke issue was discovered. Suddenly, the focus was on hurting other people. But I think the biggest gains we've had are health benefits for the individuals who smoke.

It’s very difficult to completely divorce this from one’s politics. If you are a hardcore libertarian, I don't think you should give to these particular [policy] opportunities. But I think there are some cases in which people are systematically making bad decisions, and that's not just because they live in low-income countries. That's true in high-income countries as well. So if we feel fairly comfortable with being somewhat paternalistic in the U.S. or U.K., I don't think that there's necessarily a reason to be much more cautious in other countries, unless there are particularly different social norms in those places.